I started writing this as a response on WhatsApp and soon realized that the story I had to tell was much longer and perhaps needed a bit of background, as well as greater detail than could be conveyed in a short text message. The prompt was a comment on an excellent episode of the podcast, The Seen and the Unseen, hosted by Amit Varma, which is entitled ‘The Forgotten Greatness of PV Narasimha Rao’. I highly recommend this podcast, with the caveat that if you want to become a regular listener, you either need to have an impossibly long commute, or develop a daily running habit like me, due to the extraordinary length of each episode, usually about four hours.

In this episode of the podcast, Amit Varma interviews Vinay Sitapati, the author of “Half-Lion: How PV Narasimha Rao Transformed India” (Viking, 2016). I haven’t read the book, but the interview referred to the persuasive argument (which I agree with), that PV Narasimha Rao, who was responsible for the Liberalization of the Indian economy in 1991, was truly one of the ‘Great Men’ of Indian History. Aided by Dr. Manmohan Singh as his Finance Minister, his policies broke the cycle of slow growth and transformed a government controlled economy – and was responsible for bringing hundreds of millions of Indians out of poverty. Listening to that conversation triggered memories of my brief meeting with the late former Prime Minister of India, before he ascended to that position. My first impression from that short 15-minute encounter was that this was indeed a ‘Great Man’ – I was immediately impressed with his obvious intelligence and wisdom, and went around for days telling everyone I met about it, and how completely captivated I was by his personality.

First, some background on this meeting, and how it came about.

1984 has been described as one of the darkest years in Indian history, and for good reason. In June of that year, Operation Blue Star, the military operation to storm the Golden Temple, the holiest Sikh shrine, had as its tragic aftermath, the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi by her bodyguards in October. In the days after that, the genocide of Sikhs in Delhi by rioting mobs led by members of the ruling Congress party and the benign inaction of the new government of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi is still one of most horrific and shameful episodes in India’s violent recent history. Later that year, in December, the Bhopal gas tragedy was a somber bookend to a year of despair, darkness and disaster.

On a personal note for me, the year was very mixed. Early that year, my father suffered a severe stroke, leaving him hemiplegic and aphasic for the rest of his life, leading to his early retirement. But it was also the year that I, the youngest of his seven children began my working life, in what was called India’s ‘fledgling’ computer industry. There has been a great deal written about that phase of development in India’s IT sector – with dubious theories about how the expulsion of IBM by the Janata government in 1977 may have actually spurred the development of India’s software industry and who was really responsible for the unshackling of the repressed talents of Indian programmers – but I can speak of those days from my personal experience. As an entry level worker, my observation, shared by many others in those days, credits Rajiv Gandhi and his policies for the initial growth and development of India’s IT sector.

Let’s look at the history – Rajiv Gandhi became the Prime Minister amid the chaos of his mother’s assassination and the Sikh genocide on October 31, 1984. On November 19th, the very first policy announcement of the new government was the ‘Computer Policy 1984’. The significance of that timing cannot be understated – this was barely a couple of weeks after the new PM took office, after a most traumatic transition. Of course, much of this policy had been in development since the beginning of the year – but the message that was sought to be conveyed was unmistakable. The new policy drastically reduced import duties on components and eliminated the absurd numerical limits on how many computers could be made and sold in India. It identified, for the first time, the potential of ‘software exports’ – by establishing the framework for satellite links that would enable Indian companies to work with the rest of the world. The announcement of the policy was the signal to India and the world, that India was finally waking up to the Information Technology revolution, and from my memory of the reporting in contemporary newspapers and magazines of the time, the urgency and emphasis on this came directly from the top – the new Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi.

In 1984, I joined a company called Maharastra Electronics Corporation (aka MELTRON), straight out of college, with nothing more than a vague idea that I wanted to work with computers. My MMS degree in Marketing led me naturally to jobs selling toothpaste or pharmaceuticals, but I had spurned those in favor of a poorly paid job in a government company because of my fascination with these things called computers. My job was to sell computers – which, in those days were monstrous machines the size of a couple of file cabinets, but whose capacity in terms of storage and processing power were an absurdly small fraction of the simplest cell phones that we carry in our pockets today. However, we had an advantage – being wholly owned by the Maharastra Government, we had easy access to the departments of the State government, although we also competed, poorly, in the private sector against the then behemoths – HCL and DCM, who had most of the market between them.

The announcement of the New Computer Policy of 1984 had an electrifying effect on the sleepy halls of Mantralaya, the headquarters of the state government, as did the appointment of Mr. B.G.Deshmukh as the Chief Secretary – a position with vast powers, as the head of all the administrative arms of the State Government. One particular project that I remember was emblematic of those times – the rush to ‘computerization’ was done with poor tools and inadequate infrastructure, but what we did have was great enthusiasm, and we took absurd pride in even the modest results we achieved.

Soon after his appointment in 1985, the ‘CS’ as he was referred to, placed a challenging assignment in front of us – to computerize the system for tracking applications to the ‘Chief Minister’s Relief Fund (CMRF)’. This was a fund used to disburse government aid to individuals affected by various natural or other disasters. Applications for aid from individuals – usually poor farmers and traders in the rural areas of the state – would arrive in the form of handwritten letters, which would be recorded in large ledgers. These would then churn through the gears of various ministries until they were approved, with the status scribbled in notes on those ledgers. A perennial challenge was to be able to provide the current status of an application, usually when the applicant showed up in Bombay or they made an enquiry through their MLA (their elected representative). The manual system of ledgers used was chaotic – it was impossible to search for a specific application that may have arrived months ago, and decipher the illegible notes and tell the applicant where they stood in the journey to final approval and disbursement of funds.

By this time, I had quickly abandoned any pretensions to being a good salesman, and taught myself some rudimentary programming. I designed and developed a system in dBase (a forgotten database application that only Indian programmers from the 1980s still remember), that would capture new applications to the CMRF, print out an acknowledgment to be mailed back to the applicant, enable the status to be periodically updated in the database and included some rudimentary querying and reporting functions. It was an absurdly simple system in hindsight, but it worked.

The greatest thrill from that implementation was something I experienced about a year later. I was visiting one of the offices in Mantralaya, waiting for some officer to admit me into his august presence (which was something we did a lot). I heard someone enter the adjoining office, and it was clear from his attire and language that he was from the hinterlands of rural Maharashtra. It took me a while to understand that he was there to ask about his application for funds from the CMRF and he was being given the runaround. After a while, he searched in his bag and triumphantly pulled out a piece of paper – the ‘computer parchi’ – that had his application number. Quickly, they were able to enter that number into the query screen of the DBase system I had developed, and tell him that his application had been approved, and that he would get the money in a few days. I watched him walk away with a smile, but that was hardly bigger than the smile on my face!

In May 1985, the State of Maharashtra began its year-long celebration of the Silver Jubilee of the state – the 25th anniversary of its founding. Most events in the jubilee celebrations were cultural programs – musical and dance concerts, folk arts from different parts of the state and such. Somebody in the Education Department came up with an interesting idea – to mark the occasion with a program to initiate and promote ‘computer education’ in the government school system. MELTRON was charged with implementing this program, and we put together a framework for this. We would pick a government school in each of the six Divisional headquarters of the state, and would equip that school with a computer (an IBM PC) and other equipment – which would be the first time any of the students in those areas would even have heard of, let alone seen a computer. We would also provide electronic calculators and smaller gaming consoles (the wonderful Atari 800 XL). The idea was that this would be a place where students could be brought from all the local government schools to literally ‘play with’ computers and calculators, and therefore make it easier for them to learn about them. I was charged with writing the promotional materials for the program, and I called them ‘Computer Play Centres’ – and some government bureaucrat abbreviated that to ‘COM-PLA-CENT’ – probably apt for what happened to the program later. I was able to make a quick change, and replaced it with Computer Play School.

With amazing speed, we were able to install and set up the Computer Play Schools – in Thane, Pune, Nasik, Aurangabad and Amravati. Each of these were big local events, where the local school administrators and government officials, occasionally augmented by the local MLA, attended the inauguration of the center. The climax of the program was planned to occur in December 1985, in the largest Divisional headquarters, Nagpur. And so, finally, we come to the subject of this story – because the Chief Guest for the inauguration of the Nagpur center was to be the man spoken of as the No. 2 in Rajiv Gandhi’s cabinet, the new Human Resources Development minister, PV Narasimha Rao. In September of that year, one of the many exciting policy announcements that characterized those early years of the Rajiv Gandhi administration was the consolidation of the Education Ministry with a few others into a new Ministry of Human Resources Development – the novelty and modernity of that name made it sound full of promise.

In 1985, my impressions of Indian politicians were typical of those who, like me, had grown up in Bombay. Our recent memory included the Emergency in the mid-seventies, the chaotic infighting and dissipation of the Morarji Desai-led Janata Party and the triumphant return of Indira Gandhi with her corrupt coterie of the Congress. Rajiv Gandhi and some of the new faces that entered the government with him did provide hope, but there were enough of the old guard, both in the State and Central governments. PV Narasimha Rao, from everything that I knew about him, seemed very much a part of that old Congress cohort, and my uninformed impression of him was just that – a possibly corrupt, power-hungry state politician who had made it to Delhi, and had stuck there by virtue of sycophantic loyalty to Indira Gandhi, and her son.

The Nagpur installation was quickly bedeviled by many problems. Even in December, the days were stultifying and hot, and the Patwardhan school was an ancient, creaking structure when I arrived there a week before the scheduled date (scarily, that was Friday the 13th – but I was blissfully unaware of that superstition), to see where we were going to install our shiny devices. The room that I was shown into had paint peeling from the walls, and electrical outlets with exposed wires that I was scared to go near, let alone plug anything into them. I still don’t know where I got the gumption – but I quickly metamorphosed into the ‘Bombay engineer’ mode – nobody there needed to know that my qualifications were in Statistics and Marketing Management. I confronted the local Education department head and the Principal of the school, and told them that there was no way I was plugging in these mysterious things called computers in that room. In double time, the entire room was cleaned, and ‘whitewashed’ with a slick coat of paint. I had them rip out the wires and put in new copper wires from the electrical junction box, and ordered surge protectors.

Finally, it wasn’t until Thursday morning, the day before the event, that I was able to plug in all the devices – the computers, printers, game consoles and the calculators – and test that they would even work. Then, there was more bad news. The General Manager of MELTRON, the top boss of the company suddenly fell sick and said he wouldn’t be arriving that day. My boss, the Senior Manager, had his flight canceled at the last minute and told me that he wouldn’t be there either. If you are curious about how those messages reached me in those pre-STD, pre-cell phone days, google ‘Telex’!

And so there I was, the junior-most person in the company, still barely a year and a half out of college, left to fend for myself with the highest profile dignitaries that the program had seen. I have a blurred memory of spending most of the night in that school, with a nice security guard keeping me company and bringing me cups of hot chai, testing and preparing to make sure that everything was in working order for the big event the next day.

On Friday morning, I waited anxiously for the arrival of the chief guest, trying to soothe the anxious nerves of the school principal and other local officials, all of them asking me to assure them that everything would go well. Since the whole point of this story is my meeting with PV Narasimha Rao, I will try to recount, as best as my memory serves me, exactly what happened that day.

Mr. Rao arrived at the entrance of the school, and entered the Computer Play School room, accompanied by a whole bevy of local officials. As soon as he entered the room, though, everybody fell back, because they had nothing to say about anything in the room, because they didn’t know anything about it! That was my cue to walk up to him, introduce myself and take him around.

The first stop was the highlight – the IBM PC-XT – imported from the USA. I had carefully prepared for this – I pointed to the keyboard, and said –

“Sir, can you please press this ‘P’ key – to print out the document?” – I was probably running over my words in my nervousness, but I think I got that out well enough. You have to know a little bit about computers of those days to know why that awkward request had to be made – and that will become clear below.

Mr. Rao looked at the screen and rocked me back on my heels with his next words –

“Ah – Wordstar?” he says with a smile. Why that was a surprise to me should be obvious – with all of my conceit, I had absolutely no inkling that this old politician from Delhi would know about the most popular word processing software of those days, and would be so familiar with it from just a glance at the screen!

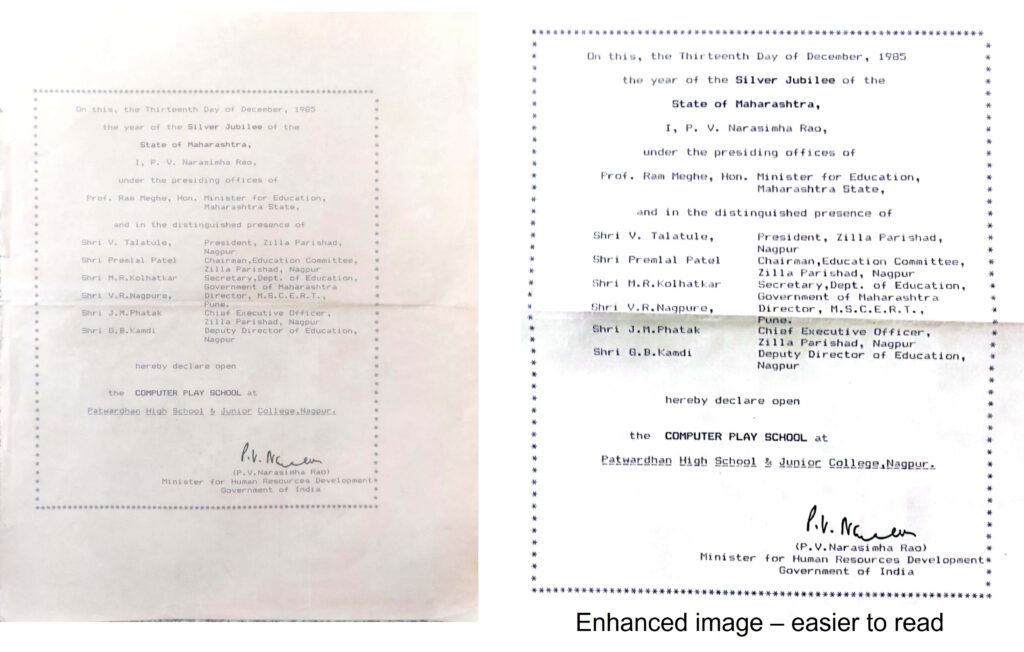

He was nice enough to do exactly as instructed – reach out and hit the ‘P’ key, which resulted in the printing of a page on the attached dot matrix printer. I took that out of the printer and laid it on the table for him to sign, and that was handed over to the official standing next to him. With amazing foresight, I had another copy of that printed document with me – and I asked him – “Sir, can you please sign this copy too, for me?” – and he obliged.

For the next several minutes, he turned his entire attention to me and asked a few questions. He looked at the logo on the computer and asked – “How did you import this computer?” At that time, IBM had no authorized dealer in India, and was still in a dubious position after their expulsion in the 70’s. I explained that Meltron was working on an arrangement with Tandon computers in the USA, to import IBM PCs and sell them in India. Nothing much came of that – but it’s a reminder of an interesting bit of trivia – long before Sundar Pichai and Satya Nadella, there was an American company headed by an Indian – Tandon – who dominated their segment, and were briefly the sole suppliers of hard disks for the IBM PC line.

Next, Mr. Rao asked me – “Are there other programs on this computer?”. I quickly brought up Lotus 1-2-3 – that hoary old predecessor of Excel, and I could see that he was just as familiar with that too. Then, he asked – “Can you do programming on this computer?”. I was now beyond excited, like a kid showing off his toys to a visiting relative – and fumbled with the keyboard, and brought up the MBASIC interpreter. Readers of my vintage will understand when I say that the most obvious thing to do after that was to load up the Bubble sort program – everybody wrote that program first. It is the most rudimentary program – to sort a set of numbers – but he followed with keen interest when I typed ‘Run’ and showed the results on the screen.

Mr. Rao moved to the next desk, on which sat the Atari 800 XL, connected to a color TV, with a game cartridge loaded in it. He seemed familiar with that too – and said that they had good games. I was making stuff up as fast as I could, babbling about how children could play games when they came there, and how it would make them want to learn computer programming. He made his way out of that room after looking at the assorted TI scientific calculators and allowed himself to be whisked out by the accompanying officials.

I went along and then heard him speak to the assembled students in a large hall. He spoke very fluently in Marathi, and I remember that he switched to equally fluent Hindi and then English as he ended his speech. I only have a vague memory of the exact contents of that speech – but I remember being very impressed with how he seemed to directly address the children. He talked about computers and how all of them would soon be working with them, and that they should all learn about them. I don’t know if the students, or even the other adults in the room understood exactly what that would mean, but of course, they all applauded.

For the next several days, after I returned to Bombay, I would bore everyone that I met with my stories of having met this extraordinarily intelligent and wise person who happened to be a politician and Central Government minister. It wasn’t just that he shattered my cynicism with his knowledge about computers, but I had this ineffable feeling, during our very brief conversation, that he was truly interested in what I was saying, was genuinely curious and was actually thinking about the merits of the program that he had come to inaugurate. He wasn’t just going through the motions. He would have been only 64 years old, just a few years older than I am now, but he made me feel this crazy excitement and pride at just being near him. His wisdom seemed to sit on him like an aura – and I know that sounds a bit fanboyish and crazy to say – but that was the feeling that I got.

I moved on from Meltron a few months after this, and I have no idea if the Computer Play School program ever achieved its objectives, or even stayed open for any length of time in those six schools. Indian politics over the rest of that decade descended into chaos with the Bofors scandal and the IPKF debacle in Sri Lanka. The successive coalition governments in the next few years only deepened our cynicism, and when PV Narasimha Rao became the compromise candidate to be PM after Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination, there really weren’t too many expectations from him. The economic liberalization in 1991 was good to see – but the increasing communalization that culminated in the Babri Masjid demolition, and the ensuing deadly riots and bomb blasts permanently changed the character of my beloved hometown, Bombay. My disillusionment and departure from India in the mid-90s meant that I did not benefit from the amazing growth that India saw as a consequence of Narasimha Rao and Manmohan Singh’s policy changes.

I have, of course, told this story to friends and family over the past 37 years, but this is the first time I have written it down. Each of us has stories about meeting celebrities or prominent persons – my stories are about attending a taping of Kaun Banega Crorepati in 2006 and having a picture taken with Mr. Sharukh Khan, and in 2007, I briefly met and shook hands with Mr. Oscar Arias, then President of Costa Rica, who is also a Nobel Peace Prize winner. But my meeting with Mr. PV Narasimha Rao stands apart as a cherished memory – because this was an actual conversation – but also more because that left such a lasting impression on me.

If anybody who reads this has contacts with newspapers in Nagpur, it would be wonderful to find out if there are archives available from the editions on December 14, 1985. One Marathi newspaper had a picture on the front page, with just the two of us – me, and the man who would be the future Prime Minister of India! I would love to get hold of that newspaper – but until then, all I do have from that day is this fading document printed on a dot matrix printer, and signed, just for me!

Beautiful. You reminded me of my meeting with APJ.

♥️